One Million Suicide Drones with Chinese Characteristics

Chinese Joint Firepower Strikes and the Future of Precision Mass

Bottom Line Up Front:

Long-range precision mass is a growing military trend globally - China has the potential to employ precision mass at an unprecedented scale.

China could use its order of 1 million one-way attack drones to enhance its counter-intervention capability.

A New Character of War

Long-range precision mass is a new form of conventional deterrence. Recent reports indicate that the Chinese government may have ordered a million kamikaze drones from Poly Technologies, a single Chinese company. Some commentators derided the reported purchase as unrealistic or propaganda. In this article, I will introduce a factory-to-target model demonstrating how this order size is realistic, timely, and may not be big enough. Let’s dive in.

Why does China need One Million Drones?

In his 2024 New Year speech, President Xi Jinping reiterated that “no one can stop China’s reunification with Taiwan.” For China to seize Taiwan by force, its military needs to conduct the largest amphibious invasion in history. Due to the complex mixture of alliances, guarantees, and other diplomatic entanglements between the United States, Taiwan, China, and other global stakeholders, it is possible that such an invasion would result in conflict along the entire first island chain (FIC) from South Korea to the Philippines and beyond. A critical component of the Chinese invasion would be the Joint Firepower Strike. Joint Firepower Strikes are how the PLA would operationalize its anti-access aerial denial (A2AD) capabilities as a counter-intervention element of the larger campaign. According to the recent Department of Defense Annual Report to Congress:

“PLA writings have long emphasized the importance of joint firepower strikes as a component of large-scale operations. Joint firepower strikes include multiple services combining to use their firepower capabilities to create substantial effect and have been explicitly tied to a Taiwan invasion in PLA writings.”

In this article, I will present a model of what a Joint Firepower Strike's kamikaze or one-way attack drone (OWA) component might look like. For model purposes, I will use a Shahed-136 style OWA. The exact type of drone the Chinese plan to purchase from Poly Technologies is unknown.

What would the one-way attack component of a Joint Firepower Strike look like?

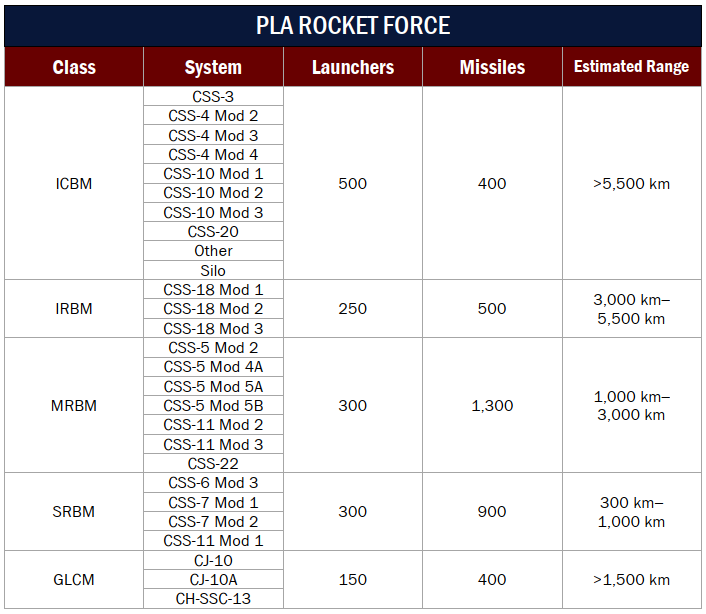

Many readers will be familiar with the PLA Rocket Force (PLARF) and their A2AD capabilities. These remain a serious threat to an adversary in the Western Pacific. However, massed OWA attacks could add an entirely new dimension to the counter-intervention campaign capabilities. The cost difference between OWA drones and other PLARF munitions means that OWA could be employed at a staggering scale.

Massed OWA attacks aim to saturate air defenses and degrade defender combat power. Constant OWA engagements deplete defender missile inventories and require extensive kinetic and non-kinetic resources that cannot be devoted to offensive action. Because OWA has been a new phenomenon over the last several years, cheap countermeasures are relatively nascent, and older, more expensive air defense systems must fill the gap.

Should the United States and its allies and partners, hereafter referred to as the Allies, intervene in a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, China would need to disrupt the Allied action across the entire FIC. Distributed OWA fires across the FIC could challenge the Allies' ability to maneuver and contest a Taiwan invasion. The map below shows notional launch areas and target areas for the OWA component of a Joint Firepower Strike.

For simplicity, I split the FIC into target areas A through J, encapsulating:

South Korea

Hokkaido

Northern Honshu

Central Honshu

Southern Honshu

Kyushu

Okinawa

Northern Taiwan

Southern Taiwan

Luzon

Each target area in the model is associated with a launch area in China, with the production factories in the Chinese interior.

Factory-to-Target Model

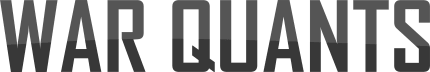

As illustrated below, the map above can be simplified into a network diagram showing OWA flow from the factory to the target area.

The factory produces units of OWA, measuring its performance with units produced per day. These OWA are then transported to magazines, where they are stored until needed in a launch area. To decrease transportation requirements, these magazines would likely be located near the launch sites for optimal distribution. When conflict begins, the OWA would be transported to a launch area and fired toward a target area. The operational performance would be measured through tons of ordnance delivered into a given target area, and operational effectiveness would be measured by the days of suppression that the Chinese could achieve with OWA as part of a Joint Firepower Strike.

Modeling the Attack

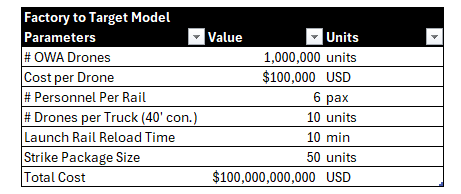

The factory-to-target model has several critical assumptions.

First, China has ordered one million OWA from Poly Technologies. Second, each OWA costs $100,000 USD. This assumption derives from a Washington Post report stating that a Shahed-136 costs Iran $50,000 to manufacture. In this case, I doubled Iran’s cost to capture increased sensor, navigation, airframe, and warhead capabilities. Next are a series of assumptions on how launch sites run and the size of each strike package. The strike package size is based on Colton Byers' analysis of Drone Carriers and the implied swarm sizes needed to inflict casualties on Surface Action Groups. The launch site assumptions are based on personal experience with rail-launched ordnance.

Manufacturing Analysis

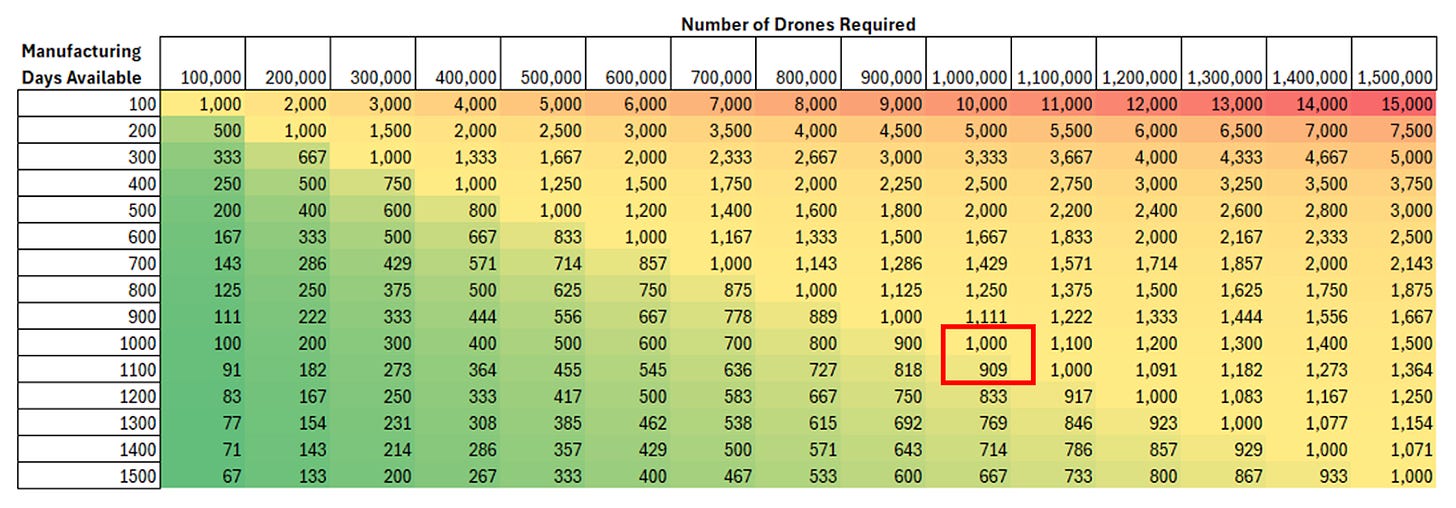

Poly Technologies does not publish its production rates or much information about its operations. To understand the manufacturing considerations, I conducted a Fermi Decomposition. The table below shows the daily production rate required, given the order size and number of manufacturing days.

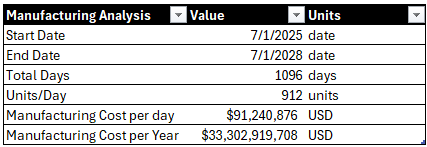

Suppose Poly Technologies wants to manufacture one million OWA in the next three years. In that case, they could begin production on 1 July 2025 and complete production around 1 July 2028. That production schedule would equate to 912 OWA units per day. For context, Tesla produced over 1.8 million cars in 2023 alone, or approximately 4,932 vehicles per day. At $100,000 per OWA, the yearly manufacturing cost would be $33.3 billion. These factors are summarized below.

In this stage, manufacturing risk is associated with facilities, materiel, and personnel. These three factors are components of the DOTMLPF-P framework used to analyze military capability integration. Meeting the quoted production numbers will require the right factory, input materials, and skilled labor. The output war materiel, OWA, must meet specific quality standards to be stored and utilized when required. Failure to bring these three factors together could result in delays and product failure.

Operations Analysis

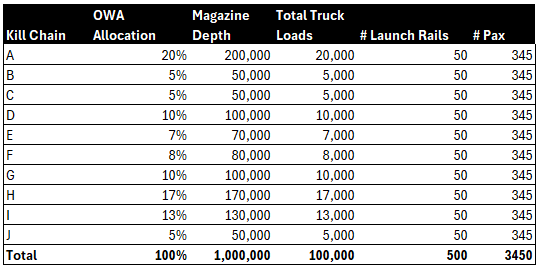

In this model, the commander allocates OWA across the different target areas shown in the OWA Strike Map, using the OWA allocations in the chart below (these specific allocations are for illustrative purposes only). Based on these allocations and an OWA order of one million units, the model computes a magazine depth requirement and the number of truckloads required to transport the OWA. For example, in Kill Chain A, the model branch related to South Korea as a target area, the commander allocates 20% of the OWA, equating to a magazine depth of 200,000 OWA, requiring 20,000 truck loads to move.

The model then uses the required number of launch rails to estimate the number of personnel needed to execute the OWA launches. The number of launch rails is derived from the strike package size – in this case, 50 launch rails. Those 50 launch rails require six personnel, or two teams of three, to service them continually during operation, along with a 15% overhead of support personnel. The model expects approximately 345 personnel to run the launch operation for each launch site. This personnel count only includes the operators who will launch the OWA sorties and, therefore, does not include logistics and other support personnel.

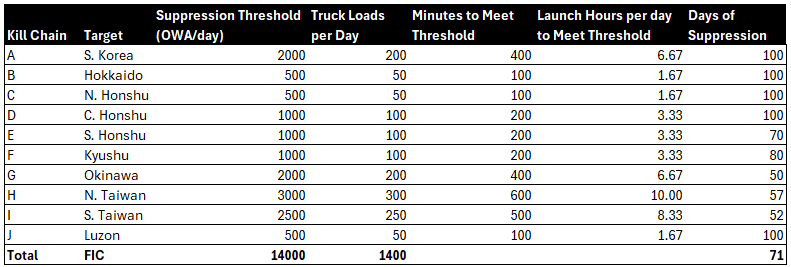

In the model, each target area has a suppression threshold: the number of OWA per day that must be fired into it to achieve the suppression measure of effectiveness. Again, the values in this example are illustrative. Based on the given threshold, the required truck loads, number of launch hours per day, and expected days of suppression are calculated.

The effectiveness of an OWA fires campaign could potentially be degraded due to personnel, doctrine, and training risks. Deconflicting, commanding, and controlling this many OWAs presents a new challenge. Likewise, identifying personnel with the potential to become skilled operators and training them to novel doctrinal standards will take time and come with its own challenges.

Model Insights:

Days of Suppression: Based on the assumptions in this model, China can achieve between 50 and 100 days of OWA suppression across the different target areas during a campaign to retake Taiwan by force. If the suppression threshold estimates were correct and the OWA optimally distributed, China would have 71 days of suppression. Due to uncertainty in the invasion campaign, this model allocates more OWAs to non-Taiwan targets. This allocation reflects the need to deconflict OWA from maneuver units crossing the strait, which results in fewer OWAs needed to suppress Taiwan forces. More than a million OWA could be required if the campaign becomes protracted. This model suggests that if China wants 180 days of suppression, it will need 2.5 million OWAs.

Resource Requirements: Achieving a one million OWA effect requires approximately a brigade of personnel to run the launch sites, 1400 trucks daily during a campaign, and $33.3 billion annually for the next three years.

Mission Effects: Campaign success for the Chinese equates to hundreds of thousands of OWA attacking sites across Allied countries and bases in the FIC. In this case, 200,000 OWA attacking South Korea alone would be horrific if even only 25% of them found their targets. From the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine by Russia to September 2024, Russia employed 8,060 OWA.

Precision mass is Conventional Deterrence: Massed OWAs allow nations to achieve devastating, distributed strikes below the threshold of nuclear conflict. As esteemed War Quant Thomas Schelling said, “The power to hurt is bargaining power.”

Conclusion

OWAs are one small part of the changing character of war. Artificial intelligence, robotics, and automation are removing the human from the forward edge of the battlefield. If China uses OWAs in its Joint Firepower Strikes in the future, the effects could be devastating. One million OWAs is a realistic goal to stockpile over the next several years as a deterrent and, if necessary, a deep war magazine. The United States, its Allies, and Partners must quickly develop countermeasures and anti-fragile systems that can withstand these onslaughts.

Read More of Our Work Here:

FPV Attack Drone Proliferation: Unfreezing Conflict in Syria

FPV Math: Precision Mass for 21st-Century Warfare

Capability Analysis: AI Machine Guns for Drone Short-Range Air Defense

Carrier 2.0: The Drone Carrier Revolution

The views and opinions expressed on War Quants are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Government, the Department of Defense, or any other agency or organization.

We need first a robust manufacturing and resources base in America before we discuss anything further.

We need the 700,000~900,000 DOD civilians that take 6 years and 27 signatures to get to contract (go and check those are the real numbers) retired and out of the loop before we discuss war.

Sorry. That’s reality.