As War Quants passes two months of weekly publishing, we wanted to take a moment to assess where we are and where we’ve been over the past eight weeks, and attempt to draw a conceptual through-line across our work to date.

Michael Horowitz's Battles of Precise Mass in Foreign Affairs has been one of the most influential articles discussing military trends to emerge in the past several months. A version of Michael Horowitz’s core thesis appeared last month in War on the Rocks, and the Net Assessment podcast recently featured the original article as a topic of discussion. It struck us that almost all of the work published by our team at War Quants over the past two months collectively supports the precision mass thesis. This article attempts to tie together our recent output on relatively narrow warfare topics and explain how the trends we have identified point towards the growing trend of precision mass in conflict.

Traditional Precision Strike

The United States has enjoyed near monopoly on precision strike weapons for decades. Initially designed to strike massed Soviet armor and mechanized forces during European conflict on a massive scale1, American precision weapons instead saw wide utilization in the Gulf War and Global War on Terror. From approximately 1990 into the early years of the twenty-first century, the United States could project force via air and sea power in any part of the world and conduct or threaten to conduct precision strikes against adversaries with impunity. As demonstrated at scale in both the 1991 and 2003 invasions of Iraq, precision strikes reduced critical regime and military infrastructure and paralyzed Iraqi resistance. Moreover, the United States employed its precision weapons from highly sophisticated platforms like aircraft carriers, destroyers, submarines, bombers, and attack aircraft whose technological complexity far surpassed that of its adversaries. The American monopoly in precision strike was short-lived. China has recently demonstrated the growing maturity of its own version of a precision strike complex with one key difference: China’s precision strike focuses less on global power projection and more on achieving regional superiority. China can now credibly threaten the exquisite platforms that the United States and its allies and partners rely on for power projection in the critical Western Pacific. Other nations like Russia and Iran have also developed organic versions of the traditional precision strike with varying levels of capability and maturity.

Surgical Precision

The realities of the last quarter century of wars abroad have also required the American military to heavily invest in an optional feature of the precision strike regime. Surgical precision capabilities enable weapons to accurately strike highly specific targets and minimize collateral damage and civilian casualties. The unmanned aerial vehicles laden with surgical strike weapons that operated abroad for decades have become emblematic of the conflicts themselves.

Relevant examples of this drone-delivered surgical precision include the assassination of Qassem Soleimani in 2020. In this incident, an MQ-9 Reaper is believed to have delivered an R9X variant Hellfire missile on Soleimani’s vehicle. The R9X Hellfire is a special variant that has no explosive warhead. Instead, it deploys rotating blades in its terminal approach to the target. This design has the specific benefit of eliminating a target and minimizing the chance of collateral damage by not utilizing an explosive warhead.

However, such operations have historically been conducted at significant expense. Estimated Hellfire unit costs range from $117,000 to $150,000, and the Air Force reports the cost of its MQ-9 Reapers at $56.5 million per unit before basing and operating expenses are considered. Operations like the assassination of Qassem Soleimani characterize the United States' conduct of precision warfare over recent years: an exquisite, low density platform delivers a precise and expensive weapon. Evidence from the ongoing Red Sea crisis suggests that America’s exquisite platforms are becoming increasingly targetable, even by relatively unsophisticated adversaries. The MQ-9 has become a frequent target of Yemen’s Houthi rebels, who are believed to have shot down numerous Reapers in the last year.

Precision Mass

What makes the new phenomenon of precision mass different? Technological advancements and cost efficiencies have enabled state and non-state actors around the globe to achieve ‘good-enough’ precision strike outcomes at scale and at highly accessible cost entry points. As the discussion in War Quants has shown, actors worldwide have increasingly invested in brute force and mass over surgical precision – in some cases, actors aggregate very large swarms of inexpensive munitions to create threshold precision effects. Examples of new precision weapons that operate in novel regions of the cost-to-capability curve include long-range one-way attack munitions like the Shahed 136, which possess sufficient accuracy to strike and inflict damage on fixed area targets like airfields, power plants, or population centers, but not to assassinate a high-value target in a moving vehicle. By contrast, first-person view (FPV) drones offer pinpoint precision at very low price points in exchange for other tradeoffs, like smaller payload sizes and the need for human operators (for now). Both of these examples differ from traditional forms of precision, but they are undoubtedly changing ground combat.

In recent weeks, the analysts and writers of War Quants have extensively explored this trend of precision mass in warfare, using a mix of empirical analysis, theory, and modeling. This work is reshared here with additional commentary to link these disparate pieces to larger trends.

New Forms of Mass and Attrition

This article focuses on the Russian employment of the Shahed-136 and Russian-manufactured variants in Ukraine and leverages empirical data analysis to demonstrate that mass makes a difference in the world of novel cost-efficient precision capabilities. Shaheds are loud, slow, and relatively easy targets for air defenses. When they were employed in low numbers for much of the first two years of the conflict, the defending Ukrainians could achieve a shootdown rate of 85%. However, as domestic production of the Russian Geran-2 variant has accelerated, and the Russians have begun to aggregate larger swarms of loitering munitions on the battlefield, Ukrainian air defenses have not been able to keep up with the increase in mass. The Ukrainian shoot-down rate has plummeted to just 58% as of October 2024. This empirical study demonstrates how relatively unsophiscated munitions that are ineffective in small numbers can be massed to overwhelm air defenses and deliver otherwise inaccessible outcomes.

This article took inspiration from recent reporting to imagine precision mass in the form of one million Chinese OWA attack drones. The PLA has reportedly ordered a drone fleet of this magnitude, but the exact details of their mission and purpose are unclear. This piece dives in to investigate the potential effects of these drones being employed in a PLA anti-access area denial counter-intervention campaign. The author shows that the PRC could feasibly achieve its goal of manufacturing and employing one million drones, and dissects the potential operational impacts at this scale. It is safe to say that such an application would dwarf all implementations of precision mass to date. As demonstrated by the large volumes of Shahed drones launched into Ukraine in recent months, the PLA could launch salvos of sufficient size to overwhelm adversary defenses across the entire first Island chain for an estimated 50 consecutive days. Combined with the PLA’s already impressive A2AD arsenal of traditional precision weapons, this one-way attack strategy could greatly enhance their counter-intervention capability.

Carrier 2.0: The Drone Carrier Revolution

This piece was preceded by a brief summary of the work of CAPT Wayne Hughes and his salvo equations. While Hughes's work was conducted during and for the traditional precision era, the models he used effectively capture the new era of precision mass. This article investigates the use of OWA drones against modern warships and explores the value proposition of a drone carrier from this lens. An attacker using sufficiently large swarms of OWA drones can ultimately overwhelm a ship’s defenses. However, the drone carrier itself is the limiting factor here for achieving this mass in fires. It is unclear whether drone carrier flight operations would be able to support the ability to mass 50 plus drones needed to begin damaging adversary ships (though this may be an issue of tactics and training). The more enduring problem is that the drone carrier itself is a large platform that presents a large target, and neutralizing the carrier will eliminate all fires in the form of drone swarms. This characteristic is fundamentally unlike how swarms can be massed from distributed launch sites from land. When applied to emerging systems and concepts, this theory and model-based approach demonstrates the applicability of precision mass munitions in a naval context and shows the pitfalls of misunderstanding the trend. Precision mass may be effective in maritime warfare, but concentrating mass on one platform may be the Achilles heel of the drone carrier concept.

FPV Drone Series

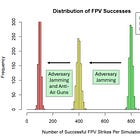

FPV drones may be what most think of when they think of modern drone warfare. These drones of the type often available to hobbyists have been adapted with improvised munitions to carry out one-way attacks. This phenomenon has brought precision strike capabilities to the tactical level of war. Tactical-level units can now target static positions or attack high-value targets like armored vehicles with pinpoint precision, challenging traditional forms of mass in ground combat. This is not quite the same surgical precision offered by many capabilities in United States’ arsenal, but it has an entirely different purpose and is a tactical game changer.

The limitations of FPV drones reside primarily in the need for operator control. Here, ranges are often limited to line-of-sight communications or control wire. Additionally, there currently exists a one-to-one drone-to-operator requirement, making it difficult to achieve swarming effects or support maneuver units with sufficient precision fires in large operations. This limitation may eventually be overcome as leader-follower and autonomous technology capabilities develop further. Technology and tactics are still evolving, but it is clear that no modern military can ignore the opportunities and threats presented by FPV drones.

The views and opinions expressed on War Quants are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Government, the Department of Defense, or any other agency or organization.

A deep field of scholarship exists on the development of precision strike, originating with Soviet analysts and theorists who defined the precision strike regime and called it a revolution in military affairs. These definitions and concepts were later adopted by Andrew Marshall and the Office of Net Assessment. As a strategic approach, it is also often referred to as the Second Offset.

Thank you for these posts. It’s a fascinating and important subject (of which I know nothing) and I appreciate the objective and analytical approach you all are taking.

The topic of “precision mass”, got me to wondering about projecting out the next fifteen years of changes in warfare capabilities & identifying regions where these new capabilities shift the current balance of powers or territorial control.

Since I’m not capable of doing anything like that, I thought to see what an advanced AI model capable of “research and reasoning” might come up with.

It’s very interesting & I’d be interested in your perspective- is there a way I could send you the output and get your assessment?

Great post. It’s just a matter of time before we see a 10x scale attack such as the Iranian attack on Israel. A question for me is how will precision mass countermeasures technology pace.